The distribution of forest tree species is expected to be affected by climate change which may have severe economic consequences (Hanewinkel et al. 2012). For example, the growth of Norway spruce is expected to suffer from water stress especially in south-eastern Sweden on sites with low water-holding capacity.[ 1] Studies assuming that the same tree species as today will be used in forestry indicate that the tree growth in Kronoberg County will in general increase under a warmer climate. Results from our simulations in the MOTIVE case study area, where we have applied business as usual forest management under both current climate and a warmer climate (A1B scenario), indicate that tree growth will increase by approximately 15% during the period 2001-2100 due to a warmer climate. The increase in growth is indicated to affect average standing volume (5%) and harvest volumes (15%) and to increase net incomes from forest operations. Due to increased growth, rotation periods will be shorter and forestry in general more intensive in terms of the number of forest operation activities per unit of time. The average number of activities per stand and year is indicated to increase by 6%, mainly in terms of final fellings and regenerations. For Norway spruce the average age at final felling under a warmer climate is indicated to reduce by seven years until the period 2071-2100. The effects of the changing climate on the forest will increase gradually which might affect also the provisioning of opportunities for hunting and recreation. Our simulation results show only small effects, however, on average moose habitat suitability index (Kurtilla et al. 2002) and recreation index (Lindhagen 2005) during the period 2001-2100.

At the same time climate change is expected to lead to increasing disturbances from extreme weather events, insect outbreaks, fungi etc. with consequences on services and benefits from the forest. While increasing growth might lead to higher financial return, the quality and or the quantity of the wood, and indeed the financial return, will reduce should insect outbreaks, wind damage or some other risk materialize. Furthermore, a changing climate might lead to effects that so far remain unidentified.

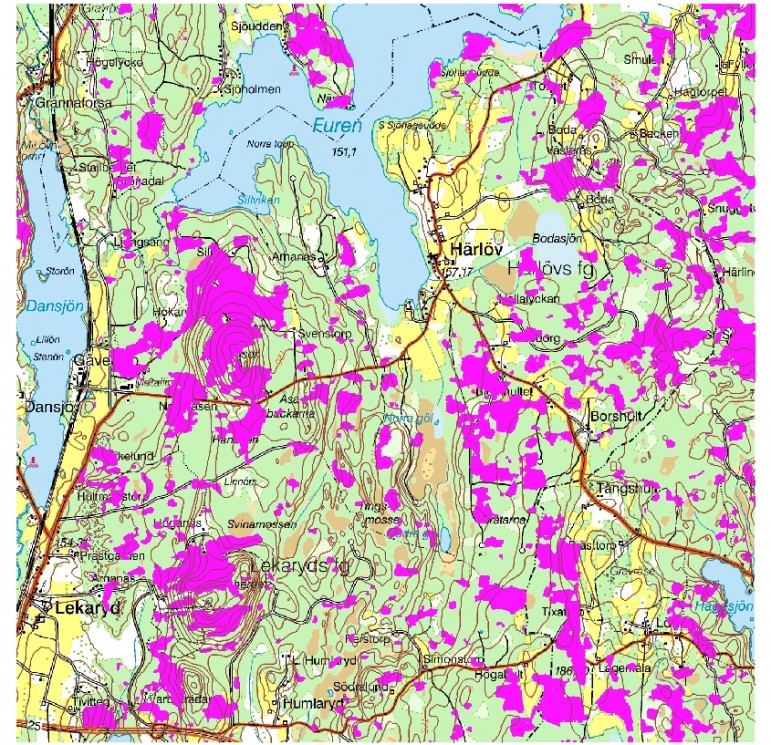

Wind damage to forests in southern Sweden has increased during recent decades (Gardiner et al., 2010). This is because of changes in the state of the forest as well as form a changing climate. Kronoberg County was the most extensively damaged county in a major wind damage event on 8 January, 2005, when damage occurred on 14.1% of its forest area (SFA 2006) (Figures SE-1 and SE-1). The wind damage was mainly done to Norway spruce (SFA 2006). More than a fourth of the forest area used for the MOTIVE simulation study was damaged during the 2005 wind damage event (based on data from the Swedish Forest Agency) (see Figure SE-1). Pervasive wind-related reduction in growth of the remaining forest during three years after the storm has recently been shown (Seidl & Blennow 2012). The growth reduction is of a magnitude similar to the total secondary damage incurred by spruce bark beetles during the corresponding period of time after the storm.